This archival content was originally written for and published on KPCC.org. Keep in mind that links and images may no longer work — and references may be outdated.

LA educators get $10 million to reinvent school for homeless kids

A team of educators with plans to launch a charter high school completely retooled to serve homeless and foster youth in Los Angeles has won $10 million in startup money over five years in a national competition — one of the largest seed grants an L.A. charter school has ever received.

The money comes from Laurene Powell Jobs, philanthropist and widow of the late Apple CEO Steve Jobs. The L.A. team was announced Wednesday as one of 10 winners in a competition she funded, "XQ: The Super School Project," which aims to redesign the American high school.

That L.A. team — lead by two former high school English teachers and incubated at the Da Vinci network of charter schools — proposed a solution to a central problem of educating homeless and foster kids: they are rarely able to remain in the same school for long, and research suggests they fall between three and six months behind every time they move.

So the school they plan to launch in fall 2017, called RISE High, will not have one primary building or a daily defined meeting time. Students at RISE will work on projects online, using devices the school will provide.

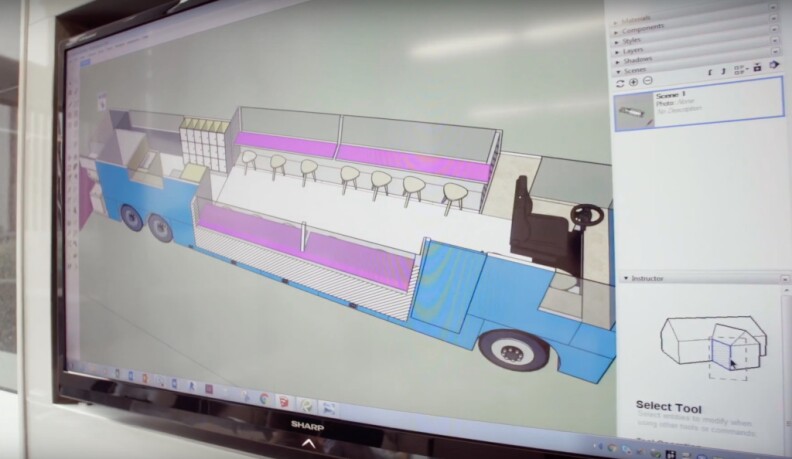

But RISE will also maintain a physical presence all over town, with locations in existing organizations and even on a modified coach bus where students can meet with teachers and get legal help, health care, laundry facilities or hygiene supplies.

"This is a model that exists outside the traditional confines of space and time," said RISE co-founder Kari Croft, who will be the school's first principal.

"Students don't have to be there from 9 to 4, all day, every day, to get credit for a class," Croft explained. "We are working with [students] to build a schedule that works with them for their lives and for their responsibilities."

Even if they hadn't won the competition, Croft and fellow co-founder Erin Whalen said they would have sought other funders for their proposal. Instead, they'll receive $2 million in each of the next five years from XQ to kickstart their operations.

It's a prize of rare size, even in L.A.'s well-backed charter school sector.

Most charter school operators in California need between $250,000 and $500,000 in startup money to tide themselves over until the spigot of state funding turns on, according to Stuart Ellis, president and CEO of Charter School Capital, a Portland-based firm that finances schools' operations and facilities.

Startup grants in the $2 million to $3 million range are not exorbitant for a young charter school's needs, Ellis said — but they are uncommon.

Even one of the city's highest-profile backers of charter schools, the Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation, has only given startup grants of comparable size to larger networks of schools.

In 2006, the foundation awarded $10.5 million to help Green Dot Public Schools open 21 new schools. The next year, Broad awarded $17 million to expand the footprint of the KIPP network of charters in L.A. from two schools to more than a dozen, foundation spokesperson Karen Denne said.

In 2007, real estate developer Richard Lundquist and wife Melanie made a 10-year, $50 million pledge to Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa's Partnership for L.A. Schools — not a charter operator, but a group that now oversees 19 L.A. Unified campuses.

It's possible to compare the XQ Super School competition to an initiative by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to support small schools. The foundation funneled $34 million in grants impacting 47 different L.A. schools — charter and non-charter — as part of that initiative between 2003 and 2010.

But unlike the Gates initiative, the XQ Super School competition was not designed to fund any one school model. Instead, from a pool of more than 700 applications, judges selected proposals that shook up the setup of the American high school, which XQ Institute CEO Russlyn Ali argued has changed very little in the century since its conception.

Among the XQ winners, "We are seeing 10 very different models, some never seen before — like a RISE in this cohort," Ali said. "And we’ll see many more as we explore in the months ahead."

The idea for RISE takes root in both Croft's and Whalen's experiences in the classroom, watching as students who didn't have stable housing situations struggled to keep up as their lives outside of school became more complicated.

It's not uncommon for homeless students to move three times in a single year, bouncing between living in shelters, motels, with family, with friends, in cars or on the streets. Though homeless students are legally entitled to remain enrolled in the same school, students' moves often make this logistically impossible.

Croft remembers watching a brilliant student she taught at a high school in East L.A. have a difficult time making it to class after a parent lost a job, the family got behind on rent and the student's housing situation became uncertain.

“The student was incredibly brilliant, incredibly capable," Croft said, "but I think when any student misses two or three weeks of school, or they're there sporadically, they start to get frustrated and start to feel like the school is not being responsive to the things that are happening beyond the four walls of the school building."

Croft met Whalen, an English teacher at another high school, while they were both serving as trainers for Teach For America. Whalen had noticed some of his students had similar problems.

“They couldn’t balance the job they needed to get to help their mother pay for rent and at the same time be in my English class," said Whalen. "So I thought, in that moment, what could we do?”

Since September 2015, Whalen and Croft have headed the team of roughly 20 educators, students and community partners that designed their solution, in the form of RISE — an educational model conceived around the idea that structure and stability isn't found in a specific school building.

"I don’t think structure and stability come from bricks and mortar. It comes from relationships and consistency in the adults that the youth is told to trust," said Leslie Heimov, an attorney who heads the Children's Law Center of California and is a member of the RISE design team.

RISE will begin with a small cohort of students and grow to serve between 500 and 550 students by its fifth year. Much of their XQ funding will help pay for additional staff members to maintain student-teacher ratios of 25-to-1 and holistic wraparound service offerings.

But there are a lot of details to sort out. First and perhaps foremost: who will give the school its charter? Croft and Whalen worked with several leaders of the Da Vinci charter network to develop their application, but it's unclear whether RISE will open as a Da Vinci school or be spun off on its own. The Wiseburn Unified School District authorizes Da Vinci schools.

The school's founders still have to identify where they want to open brick-and-mortar sites. They've identified several potential partners — including the Children's Law Center and School on Wheels, which provides tutoring services and after-school programming for homeless students — but have yet to formalize how these partners will be involved.

RISE's founders also haven't figured out which online materials or software they want to use, which they acknowledge will be critical — research shows schools that blend online and in-person learning have mixed results, and their success will be all in the execution.

"That was a similar concern we have in figuring out how do we create a hybrid model that is really rigorous and doesn't just put kids in front of a computer all day, every day," said Croft, "because we don't think that works. We think online learning is a powerful tool if it's used in conjunction with other powerful tools."

While the founders have $2 million at their disposal in each of the next five years to sort out these issues, School on Wheels executive director Catherine Meek said that money will go quickly.

"I wish we had another $2 million," said Meek, who helped craft RISE's application. "But when you're trying to do what RISE is trying to do, it's not that much money."

But Whalen and Croft say they intend to craft a school that will be able to outlast the prize money and serve as a "proof point" for others trying to serve homeless students.

"This can happen for all students and all communities," Whalen insisted, "and this can be a system that can work.”