The Myth of the 'Miracle School'

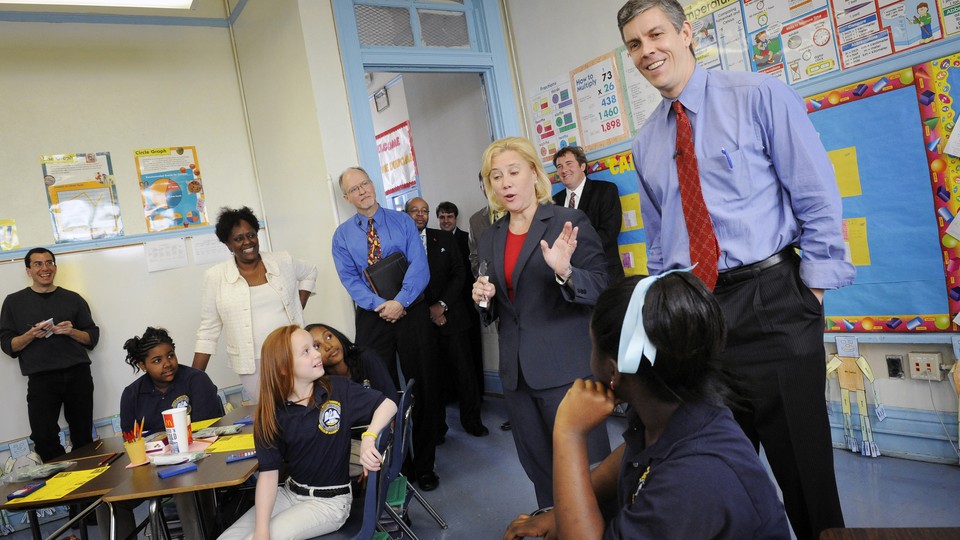

Former U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan examines the issues at the heart of the charter-school debate.

In the field of education, success is too often an orphan while failure has many fathers. The stories of the high-performing charter-school networks featured in Richard Whitmire’s important new book, The Founders: Inside the revolution to invent (and reinvent) America’s best charter schools, provide a welcome antidote to the pernicious notion that high-performing schools for disadvantaged students are isolated flukes, dependent on a charismatic educator or the cherry-picking of bright students. Whitmire’s account reveals the secret of the sauce: What is it that schools can do at scale for children to close achievement gaps, even in the face of the real burdens of poverty?

As the CEO of the Chicago Public Schools, and later as the U.S. Secretary of Education, I had the good fortune to visit dozens of gap-closing charter schools, including many of the charter-school networks featured in Whitmire’s account. I always came away from those visits—as I do when I visit any great public school—with both a sense of hope and a profound feeling of respect and gratitude for the school's educators and school leaders.

At the same time, it was clear to me on these visits that running a high-performing charter school is anything but simple or for the faint of heart. It takes courage, a caring connection with students, and a tenacious commitment to equity. It takes smarts, and expertise about how children learn. And it takes talent. And for the sector, it takes courage.

I have yet to visit a great school where the school leaders and teachers were content to rest on their laurels. I have never heard a charter-school leader describe his or her school as a “miracle school” or claim to have found the silver bullet for ending educational inequity. The truth is that great charter schools are restless institutions, committed to continuous improvement. They are demanding yet caring institutions. And they are filled with a sense of urgency about the challenges that remain in boosting achievement and preparing students to succeed in life.

This year marks the 25th anniversary of the passage of the first state law authorizing charter schools—which came about, in no small measure, thanks to the advocacy of Al Shanker, the legendary labor leader of the American Federation of Teachers. Twenty-five years later, it seems fitting to take stock of the successes and failures of the charter-school movement—and to ask what challenges the next 25 years will bring.

In their first quarter-century, charter schools dramatically expanded parental choice and educational options in many cities. What was once a boutique movement of outsiders now includes more than 6,700 charter schools in 43 states, educating nearly 3 million children. But the most impressive accomplishment of the charter-school movement is not its rapid growth. Nevertheless, what stands out for me is that high-performing charter schools have convincingly demonstrated that low-income children can and do achieve at high levels—and can do so at scale.

When I was at CPS in Chicago, people used to warn me that the city could never fix the schools until it ended poverty. For the record, let me stipulate that I am a huge fan of out-of-school anti-poverty programs. CPS dramatically expanded the number of school-based health clinics, free eye-vision services, and dental care. I was virtually raised in an out-of-school anti-poverty program: my mother’s after-school tutoring program on the South Side of Chicago.

Yet I absolutely reject the idea that poverty is destiny in the classroom and the self-defeating belief that schools don't matter much in the face of poverty. Despite challenges at home, despite neighborhood violence, and despite poverty, I know that every child can learn and thrive. It’s the responsibility of schools to teach all children—and to have high expectations for every student, rich and poor. I learned that lesson firsthand in my mother’s after-school tutoring program—and I saw it in action in my visits to many of the gap-closing charter schools featured in this book. High-performing charters are one more proof positive that, as President Obama says, “the best anti-poverty program around is a world-class education.”

Sadly, much of the current debate in Washington, in education schools, and in the blogosphere about high-performing charter schools is driven by ideology, not by facts on the ground. Far too often, the chief beneficiaries of high-performing charter schools—low-income families and children—are forgotten amid controversies over funding and the hiring of nonunion teachers in charter schools. Too often, the parents and children who are desperately seeking better schools are an afterthought.

Despite the bloodless, abstract quality of much of today’s debates on charters, the ideologically driven controversies won't end anytime soon. Advocates and activists will continue to care about whether a high-performing school is identified as a charter school or a traditional neighborhood school. But it is worth remembering that children do not care about this distinction. Neither do I. Our common enemy is academic failure. Our common goal is academic success.

There is nothing inherently good or bad about a charter or any other school and, as I said in a speech to charter advocates back in 2010, it is absolutely incumbent on the charter sector to be vigilant about policing itself and closing down low performers. The only thing that matters is if a school is a great school. It doesn’t matter to me whether the sign on the door of a school has the word “Charter” in it, and it doesn’t matter to children. Nor does it matter to most parents.

This article is excerpted from Richard Whitmire’s book, The Founders: Inside the revolution to invent (and reinvent) America’s best charter schools.