Twenty years ago, Andre Agassi was at the top of his game — a highly ranked tennis pro with an Olympic gold medal by the age of 26.

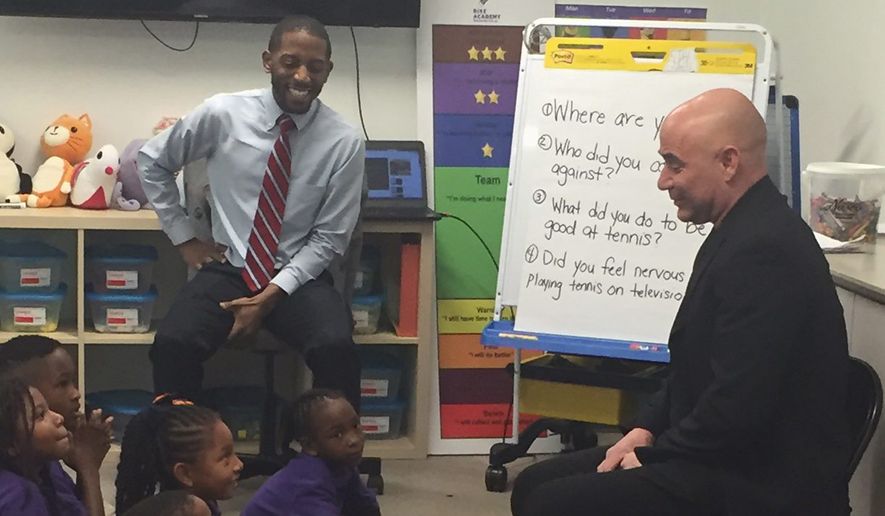

But students and teachers at the Rocketship Rise Academy in Ward 8 recognize Mr. Agassi as the man who founded their charter school, which joins 117 other publicly funded, privately operated education centers in the District.

After a rocky start in the face of opposition from D.C. Public Schools, charter schools have made a place for themselves in the city since 1996, attracting investment from an array of nonprofit groups to provide education to more than 41,000 students in all eight wards.

This year, the Turner-Agassi Charter School Facilities Fund partnered with Rocketship Education, a nonprofit network of elementary charter schools, to open its first school in the District of Columbia.

The Andre Agassi Charitable Foundation “was always focused on kids, but I ended up feeling that we were just sticking Band-Aids on real issues, and the only way to make real change was to educate,” the former tennis champion said. “I saw a show on ‘60 Minutes’ about a great charter school operator, and it inspired me to set about the herculean task of doing it in Las Vegas, my hometown.”

His vision became a reality when the Andre Agassi College Preparatory Academy opened its doors in 2001. Since then, Mr. Agassi has been involved in the development of 69 charter schools in disadvantaged neighborhoods throughout the U.S.

When charter schools were introduced in the District 20 years ago, parents, educators and lawmakers were uncertain how they would affect traditional education. Critics said charter schools would siphon off funds from traditional public schools and would not be subject to oversight by city administrators.

But today, under the supervision of the D.C. Public Charter School Board, the city’s 118 charter schools serve about 45 percent of the District’s student population, ranking fourth in the nation in charter school enrollment. Neighboring Virginia has nine charter schools, and Maryland has 51.

Despite their success, charters face a unique set of obstacles. After receiving permission to start a school, charter organizers must secure funding for facilities, spend countless hours recruiting, find transportation for students and adhere to strict oversight from local boards.

Still, results from the second year of standardized testing by the Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers show charters outperforming traditional public schools in elementary and high school education throughout the District.

“Not all charter schools are outperforming district peers. Matter of fact, 85 percent do not, to be clear,” said Mr. Agassi. “But the top 15 percent, Rocketship being one of the gold standards, really do outperform by miles.”

‘We can do anything’

Located in the Woodland Terrace neighborhood, Rocketship Rise Academy started its inaugural school year Aug. 22 with 433 students in pre-K through second grade. The 58,598-square-foot building, developed by Turner-Agassi, has 26 classrooms, three special education classrooms, one learning lab, two cafeterias, a gymnasium, a nurse’s suite, multiuse agora space, two playgrounds and a nature trail.

Tanjanyca Fairley, a mother of two “Rocketeers,” said her children thrive under the academy’s hands-on, technology-based teaching.

“The quality of the education, the dedication to the community and the involvement with the parents have been incredible,” said Ms. Fairley. “Rocketship has given us new hope for our children here in the Southeast area.”

Since Rocketship announced plans to build a campus in Ward 8, parental involvement has been a top priority. Southeast native Patricia Coates, whose great-granddaughter attends the school, was one of several involved in interviewing prospective teachers.

“Education is very important to me,” Mrs. Coates told the crowd the ribbon-cutting ceremony Tuesday.

Rocketship’s plan appears to be working. Students in the charters’ Bay Area network ranked in the top 10 percent in math and English language arts among California schools serving similar demographics during the 2015-2016 year.

At the Oct. 17 meeting of the D.C. Public Charter School Board, Jacque Patterson, Rocketship’s regional director and a 21-year resident of Ward 8, said the organization plans to open a second campus in Ward 7 next fall.

Nonprofit groups are working to open and expand charter schools in the city as demand remains high.

When Washington Leadership Academy opened its doors in August, the technology-focused high school charter had dozens of students on a wait list. The school operates in a remodeled building that once housed priests studying at Catholic University.

The school started its first year with over 100 ninth-graders. Another grade will be added each year.

In addition to basic courses, the school teaches students how to write computer code and use drones, which Principal Joey Webb says is a big draw. Giving students the skills to succeed in a technocentric society is one of the school’s main goals.

“College has always been a big priority for me,” said student Sheyla Gyles. “At first, I wanted to just go somewhere local like American University, but since I started school here, I now feel like I can go to Princeton. The way we’re taught makes us feel like we can do anything.”

Working together

For underprivileged students, building personal relationships and increasing confidence are imperative to success. Horton’s Kids, a community-based group, has worked with pre-K through 12th-grade students from traditional and charter schools in Ward 8’s Wellington Park neighborhood to do just that.

The nonprofit has provided after-school academic tutoring, extracurricular activities and health-based assistance for 27 years. Executive Director Robin Gelinas Berkley said charter schools have had a big impact on at-risk children.

“What I often observe is the change in attitude a child will have when they go from a traditional public school where there’s a lot of children and limited resources to a charter school with a completely different approach,” said Ms. Gelinas Berkley.

“The high expectations and personalized education give them a greater sense of ownership over their education. For kids that are living with chaos and lack of structure in their daily life, feeling a sense of ownership over your education, even for kids at a young age, makes a big difference.”

One of the biggest challenges charter schools face is bringing children to the education level where they should be.

“We knew on paper that we’d have kids at a third-grade level, but when you look at that kid, you get to know them and think, ‘How is this possible, and how are we going to get you to college?’” said Stacy Kane, co-founder and executive director of Washington Leadership Academy.

“And who the heck let this happen?” Mr. Webb said. “It makes me really angry to think that this can even happen.”

The Office of the Deputy Mayor of Education launched a cross-sector collaboration task force this year. The 26-member group — comprising parents, community members and district agency representatives — will work for nearly two years to improve traditional and charter schools.

“The city is best served by having strong charters, as well as strong traditional public schools,” said Scott Pearson, executive director of the D.C. Public Charter School Board. “This task force will achieve creative solutions to issues that all schools have to address. It’s only by working together that we can have the biggest impact on students.”

D.C. public and charter schools have worked together for years on initiatives such as teacher training. As charter school enrollment increases to nearly half of the city’s 88,000 students, officials say working together is a top priority for the benefit of all.

“I’ve seen firsthand the progress that’s happened in our schools,” said Hanseul Kang, the District’s state superintendent of education. “Enrollment is up in both sectors, and it’s really exciting.”

In a second-grade class at Rocketship, the progress speaks for itself.

“Who wants to go to college?” Mr. Agassi asked the class of 15 minority students.

Every hand shot into the air.

• Julia Porterfield can be reached at jporterfield@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.